A guide through Security Token Offerings (STO) — part 2: The STO process

The following article is the second part of a series of three. It is addressing interested investors, issuers, banking & legal experts and tech-savvy individuals alike.

Introduction

The tokenization of an asset or security is first and foremost a digitalization project. Blockchain (respectively decentralized ledger technology) and its nature of decentralization represent only one part of the whole implementation of such a project. Nevertheless, the aspect of decentralization is key to eventually leverage on the digitalization of securities / assets. It is eventually the key driver for the implied benefits of digital assets (e.g. efficiency gains, higher liquidity and more transparency — see part one of this series of articles). To sum up, a security token offering (STO) combines various digitalization elements with decentralized ledger technology into a holistic process.

However, how does that work exactly and what does it include? The process can generally be split into three main phases: 1. Preparation, 2. Execution, 3. Continuation. Each phase can be subdivided into multiple aspects. Ideally, all of these should be addressed in every security token offering, especially for the tokenization of equity and debt capital. Figure 1 shows a model of this simplified tokenization process. Please note that in practice some aspects may be covered in other phases.

Definitions

Please note that even though the expressions are often used interchangeably it is important to point out the difference between a tokenization and a security token offering. The term “tokenization” generally refers to generating a digital token in a distributed / decentralized system. The article at hand focuses only on security tokens (i.e. utility or payment tokens are excluded). The tokenization of securities can apply to the following two cases:

- A company that is digitizing existing securities (i.e. taking existing securities and transforming them or part of them into a new digital, distributed form).

- A company that is issuing new capital in a digital, distributed form (e.g. in the case of equity as a capital increase). This can also be called security token offering (STO).

This article deals mainly with the latter case as it for example includes the financial structuring aspect, which is only part of a new financing project such as a capital increase of an established company or a start-up financing. Furthermore, this article often points out the underlying requirements of an equity token. The tokenization of other assets or securities might differ. (By the way: Asset tokens are as a rule treated as securities by FINMA.)

The STO-process in detail

The following list shall illustrate the non-exhaustive contents of each aspect along the STO-process (see figure 1 above). Defining the optimal and recommended implementation option is an essential part of the research project co-financed by the Swiss Innovation Agency, Innosuisse. This development process will result in the tokenization standard, which is expected to be published later this year.

Phase 1: Preparation

The starting point for a security token offering is a need for financing combined with an initial idea to pursue this undertaking in a digital way. Possible reasons for a tokenization have been discussed in part one of this series (efficiency gains, higher liquidity and more transparency).

Financial Structuring

The process of every security token offering starts as any other traditional financing with the basic definition of the underlying business case and its financial implications:

What is the financing needed for and in which timeframe must it be available? What is the company willing to offer in return and what might possible investors ask for? What does this mean for existing creditors and shareholders of the company and is the financing compatible with the company’s current financial situation?

These and more questions need to be addressed before starting to think about a digital representation of a financial asset in the form of tokens. To sum up, every tokenized security is still a security and should therefore undergo a traditional financial structuring. Presenting the underlying business case in not only important for the financial structuring but also has an impact on the whole execution of the tokenization.

Ecosystem Evaluation

When the issuing company has put together a sound business case and decided on a respective financial structure (e.g. a capital increase by issuing new registered shares for a market expansion) a first evaluation of potential business partners follows. This is the first time the new aspect of tokenization really comes into play.

A tokenization generally includes the interaction and cooperation of different market participants forming an ecosystem (mainly: technology provider, financial intermediaries and legal experts). The security token market is still in its infancy and therefore the choices are to some extent limited. However, there are more and more ecosystems around different partner networks evolving. Not all of them are totally interoperable with other ecosystems yet, which is one of the key factors for a broader market adoption of security tokens in the future.

To evaluate an ecosystem, issuers need to consider not only technical and legal aspects, but also the interoperability and scalability of an ecosystem. The choice eventually will also be affected by the kind of investors expected (retail or institutional, national or international) and the requirements for secondary markets (see below in phase three).

Phase 2: Execution

Phase two describes the core principles of the primary market aspects of an STO-project. It includes the due diligence processes a tokenization platform should include and make available to its clients and their investors. Moreover, it shows different possible characteristics of data structures (e.g. which information is saved on-chain or off-chain) and who is responsible for which steps in the tokenization process (i.e. governance).

Issuer Onboarding

The first of these due diligence processes concerns the issuer. It is advisable to any tokenization platform and the involved financial intermediaries to carry out a thorough issuer onboarding. This includes for example background checks on the main exponents and existing shareholders of the company. As in any other financial transaction the building of trust is essential. Thus, making sure the issuers fulfil not only market but maybe also individual requirements is of great importance for establishing a broader and wider accepted security token offering market in Switzerland.

The issuer onboarding also consists of collecting official information about the issuing company. For example the signatory powers derived from the commercial register will form the basis for defining certain compliance processes in the subsequent aspects of «governance».

Origination

The term “origination” refers to the legal establishing of the actual assets or securities and includes all kind of preparatory work. Generally, the issuer must adapt its constitutive documents. In the case of the issuance of new shares which are then tokenized the issuer has to make sure for example that its articles of association exclude the right of shareholders to request a physical delivery of their share certificates. Another point would be that the possibility of uncertificated register securities explicitly has to be stipulated in the articles of association.

Moreover, the issuer or its legal advisor must prepare the necessary issuance documents. Depending on the size and the addressees of the issuance this might also include a prospectus.

Excursus:

In Switzerland, there is no need for a prospectus for issuances:

- to less than 500 addressees (i.e. not public).

- only directed to professional investors.

- with a minimum investment ticket of CHF 100’000.

- of less than CHF 8’000’000 total capital raised (in 12 months combined).

- employee shares.(for details check out this article)

As pointed out above, there are some additional aspects to consider due to the tokenization of the asset or security. However, there is no shortcut on the legal constitutive process of the underlying itself. Tokenizing assets is not a way to circumvent legal requirements, as the tokenized securities are just a digital representation of the underlying asset.

Nevertheless, the new DLT law in Switzerland (partially came into effect as of 01/02/2021) offers the possibility of issuing uncertificated register securities (in German: Registerwertrechte). One of the key adjustments made by the new law is the removal of the need for a written cession. This way, uncertificated register securities allow for a frictionless digital transfer of security tokens.

There are other legal issues, which may also affect this part of the STO-process (e.g. the question of wether the underlying falls under the Swiss collective investment schemes act or not?). Thus, the goal for any issuer and/or technology provider is to be able to deliver not only a sound business case but also a matching, well drafted and transparent legal documentation.

Governance

Establishing transparent, reliable and trustworthy governance principles is key in every tokenization project. It is not only a nice-to-have attribute but is also legally required (e.g. by the new Swiss DLT law — also check out the respective remarks in the latest report by the Swiss Blockchain Federation).

For example, it has to be ensured by technical or organisational measures that the register cannot be manipulated. This especially includes answering questions like: Who can issue a token? How can it be issued? How can a token be frozen? How can it be locked up as a collateral? Which other roles are foreseen in the smart contract (on-chain) or outside of the DLT-world (off-chain)? How can the holders of these roles be changed? What rights has each role? Who makes sure that the role holders are correctly mapped to the corresponding official registries (e.g. commercial register)?

The technical representation of all these rules is very well possible but it can quickly become very complex. This fact causes a higher risk of errors in the code, which could then become a major risk factor for the integrity of the tokenization project itself. Thus, it is crucial to find the right balance of how the governance processes are implemented. During all of this, it is important to keep an eye on the proportionality of the respective measures; e.g. for which risks is it worth going the extra-mile and defining complex governance processes (be they on-chain or off-chain)?

Payment Options

A seamless integration of payment systems is key for any tokenization ecosystem. Hence, it is important to look at the different options (see figure 3). The depth and range of integrated payment systems eventually has an impact on the user friendliness and attractiveness to current as well as future shareholders and investors. Generally speaking, the less (decentralised) automation the more (centralised) governance and checks are needed to guarantee a secure transfer of digital assets.

A first distinction has to be made between FIAT and crypto payments. While for most of the ICOs between 2016–2018 crypto payments were almost a must-have, nowadays, STOs mainly rely on FIAT payments. FIAT does not necessarily mean the involvement of an intermediary system; more important than the segregation between FIAT and cryptos is the level of digital integration (i.e. how automated the delivery versus payment process is structured) of the respective payment medium.

In the case of a cash transaction this process comes down to a physical exchange of the payment, while the token transaction has to take place in sequence. This kind of transaction postulates a certain amount of trust between the two parties and can be seen as a form of peer-to-peer transaction. An example could be a friend selling another friend some of the tokens he/she owns. Even though the tokenization of assets allows for the instant transfer of the purchased assets, cash as a payment method will presumably never play a major role in security token markets.

Thus, for higher volumes of transactions other options are needed. Currently, the most prominent case lies in integrating bank payments into a tokenization system. This could for example be done via bank transfers or credit card payments. However, this system requires some kind of governance structures for the payment process (i.e. delivery versus payment, DvP). A well governed tokenization system should include a trustworthy third party (intermediary) to make sure the off-chain payment (off-chain as it is done outside of the blockchain via bank transfer) and the on-chain transfer of the asset are carried out according to the transaction agreement. This function could be carried out by a bank or another financial service provider.

Interestingly, if a payment via cryptos (e.g. BTC or ETH) is foreseen in a tokenization system the mechanism is often the same as mentioned above (i.e. similar as payments via bank transfer). This means, that even though the payment is in crypto, it is not directly settled on-chain against the security token. Rather, the payment aspect is also handled off-chain (respectively not linked to the smart contract of the security token) and therefore requires an intermediary respectively a manual exchange.

The goal should ultimately be to settle delivery versus payment on-chain. That means that the payment (be it in form of a crypto currency or a FIAT backed digital asset) as well as the security token are both on the same (public) blockchain. This way, delivery versus payment could be fully decentralised and would be automated via a smart contract. There would not be a need for an intermediary anymore.

Settling a transaction on-chain with the underlying native token (e.g. ETH for an Ethereum based security token) would be doable already. Due to the high volatility of the ETH this would cause quite some exchange risk for the transaction (besides the current high gas price). Including an exchange rate oracle could be an option but this would just introduce another intermediary (process).

Therefore, the ideal way to settle transactions would be via a digital FIAT currency (basically a crypto currency backed with FIAT, which are also called stablecoins). There are already several providers of private stablecoins and numerous central banks around the world are currently assessing the merits of public stablecoins or central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). At the moment however, these projects are not yet ready for mass adoption. Nevertheless, the importance of broadly accepted digital FIAT currencies cannot be emphasized enough.

Investor Onboarding

Before going into the details of investor onboarding in a security token offering it is worth looking at how this process works in a “traditional” environment (of a non-listed company). Because, as we have seen before, the rules for the origination of a security / asset did not really change. Hence, let’s take the case of a capital increase as an example (the process of founding a start-up company is basically the same):

- After financially structuring the capital increase and preparing the issuance from a legal perspective, the financing seeking company opens a capital payment account, which is a special form of an escrow account (in German: Kapitaleinzahlungskonto) with a bank of their choosing. The hurdles to open such an account are rather low.

- Potential investors receive information about the issuance and if they decide to invest they sign a certificate of subscription and place their respective deposits into the escrow account.

- After having reached the financing target, the issuing company originates the capital increase at the commercial registry. The statement of the capital payment account serves as proof for the additionally raised capital.

- With the adjusted entry in the commercial registry (showing the increased capital), the company is now able to transfer the raised capital from the blocked escrow account to a regular current account.

- To be able to do that the issuing company has to itself undergo an onboarding process with its bank.

So far so good. This process is quite straightforward and works well in practice. Though historically, issuers as from our example did not always pursue in-depth KYC checks on all their investors. There was no need for it and most often the issuer knew their investor base well anyway as it was generally limited to a small number of investors. Furthermore, transactions on the (almost non-existing) secondary market were seldom. Lastly, not all of the equity was raised as registered shares but also as bearer shares; so there was even less of an incentive to identify and register ones shareholders.

However, through tokenization and its expected efficiency gains as well as higher liquidity (see the first article of this series of articles), smaller investment sizes (fractional ownership), more transactions and a more global investor base could be seen in the future. Thus, past processes might need adjusting to some degree.

Identification of counterparty and source of funds

Looking back just a few years, initial coin offerings and cryptocurrencies did not always have the best reputation. One of the most common criticisms was that they enable money laundering, terrorism financing or other prohibited financial transactions. As security token offerings are getting more popular the market participants must ensure that such activities are prevented in the digital asset space going forward. This basically includes two parts:

- Identification / know your customer (KYC)

Knowing who exactly is the counterparty of a transaction and eventually the beneficial owner of the asset / security. Are these exponents sanctioned or flagged in any way (e.g. as politically exposed persons (PEP) or as having a criminal record)? - Source of funds / anti-money laundering (AML)

Knowing and qualifying the source of funds. Are the sources of the funds legitimate and do not include any illegal or sanctioned sources?

But who is actually responsible for carrying out which kind of due diligence processes during the investor onboarding?

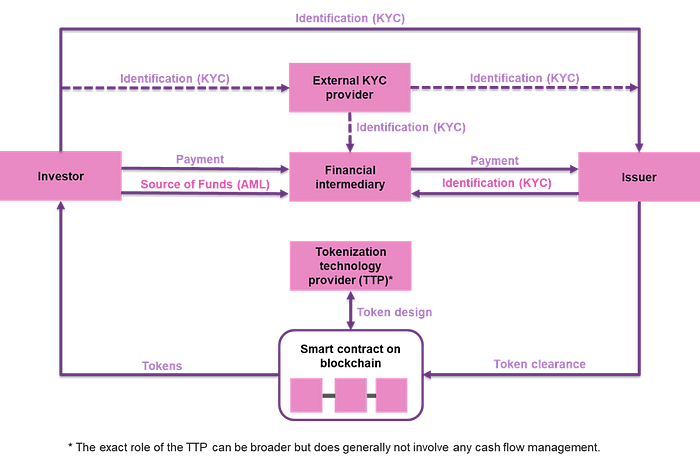

Generally, there are four parties involved in the investor onboarding: the investor, the issuer, the tokenization technology provider and the financial intermediary (for FIAT-payments a bank and for crypto-payments for example a crypto-broker). Additionally, in certain cases an external KYC provider might assume parts of the investor onboarding processes. Figure 4 and the following explanations describe the relations between these parties in the case of a payment structure with an intermediary (for more details see the section on «payment options»). Please note that the focus lies on the primary market. However, the information structure in the secondary market does not materially differ in terms of KYC and AML.

The issuer’s goal is obviously to fund a project and therefore eventually receive payment from its investors. In the case of a security token offering the issuer itself is not subject to direct (or indirect) oversight by FINMA under the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA). The same generally applies to the tokenization technology provider if no payments are processed through its books. However, the outlined structure involves a financial intermediary, which clearly has to comply with the AMLA. Thus, the financial intermediary will need to identify the source of funds as well as (at least) the controlling persons of the issuing legal entity (see «Form K» of the Swiss Bankers Association). The information about the investors respectively the future shareholders can usually be obtained through the issuer (which is or will be the client of the financial intermediary).

As through tokenization the number of investors generally is higher (and often includes cross-border aspects), the need for professional external KYC providers has risen. These providers try to automatize the collection and combination of KYC-profiles and allow the outsourcing of some of the compliance work. However, the final assessment (as well as the responsibility) of the information stays with the financial intermediary.

Even though strictly interpreting the law KYC duties are mainly in the hands of the financial intermediary, the issuer itself has to take an active role regarding KYC processes itself. Considering the past experiences during the ICO wave, the reputation and with it the future of distributed financing via tokenization is at stake. Therefore, it is more important than ever that all tokenization projects have thorough know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML) processes in place.

Basically, all investors / token holders (respectively its beneficial owners) need to be identified and the source of funds has to be clarified according to their risk profile. To be able to exercise the full rights (such as voting rights and dividend payments) the identification and registration of the respective shareholder is indispensable anyway (in the case of registered shares). Moreover, additional checks (e.g. in sanctions and PEP databases) on the potential investor should be carried out. Only then, shall a potential investor get access to buying and selling security tokens (i.e. shall be whitelisted).

Whitelisting describes the process of allowing a user (respectively investor or prospective token holder) to interact with the smart contract. The main goal of a whitelisting is making sure the users are properly identified. Thus an essential part of a whitelisting-process is normally dedicated to registering the investors.

The actual “white list” includes the names, addresses and birth dates (minimum requirements) of all token holders / investors and matches the token holders to their tokens respectively their wallet addresses.

Due to data protection regulation, the “white list” is kept off-chain (i.e. not on the blockchain but in a separate database). Some approaches have tried to keep personal data in an encrypted form on-chain. However, as transactions in a blockchain are immutable the risk persists that at some future point, a once seemingly bullet-proof encryption could be deciphered.

In practice, various ways of handling the identification of token holders can be observed. The most prominent option is to include a technical requirement for a completed whitelisting-process in the smart contract. This means that the token can only be transferred by and to identified and registered (i.e. whitelisted) token holders / users. On the other end of the spectrum lies the option to not include such a technical transfer restriction but to require identification only for certain actions (e.g. exercise of shareholder rights). This means that the token can be freely transferred to any person having access to the underlying blockchain protocol (e.g. on Ethereum) and that tokens can for example be traded on decentralised exchanges without any hurdles. Only if the buyer of the tokens wishes to exercise his or her shareholder rights he or she needs to be identified. There are however also possibilities that combine elements of both extremes. From an ideological perspective, the option without transfer restrictions is a lot closer to the original thought of distributed ledger technology. However, from a regulatory perspective, this option also bears a lot more risks.

On-Chain

The aspects of On-Chain and Off-Chain describe the components of the technical architecture of a tokenization project. On-Chain components respectively its scripts (in the form of smart contracts) represent the backbone of every tokenization project. A smart contract is a piece of software that is stored on a distributed ledger (e.g. a blockchain). This characteristic of decentralization ensures that the transaction records are tamper proof (depending on the exact design of the underlying DLT solution). Previous transactions are immutable and double spending is not possible.

A smart contract of a security token could cover a very broad range of governance rules. For example, the signatory powers for all kind of corporate actions can technically be reflected. Roles could be defined and private keys to exercise the respective rights and duties could be distributed accordingly. One challenge lies in managing these systems and making sure all parties understand the processes, keep their keys safe and are actually willing to adapt to a digitized process. A pragmatic solution could include appointing an independent notary, who must sign-off important corporate actions according to laws and the articles of association. This way, a minimum level of checks and balances in terms of corporate governance can be ensured.

Another point to consider is the cost of transactions. Every additional function of a smart contract increases its complexity. And the more complex a smart contract is the more expensive the deployment and usage becomes (e.g. in the case of a token on Ethereum measured in «Gas»). Lastly, every added complexity also bears additional risks for exploitation of the code. Audits are one way of ensuring the soundness of the code. However, obviously these costs increase as well with the extended amount of code. Thus, every tokenization project has to find the right balance of on-chain and off-chain processes.

Off-Chain

Off-Chan-components describe all elements that are not directly deployed, stored or calculated on the blockchain (respectively another form of DLT). This can for example include a database that keeps the records of all personal data of the investors. This database is generally not public. It maps the token holders to their respective wallet addresses and in the case of an equity token allows to compile the shareholder registry at any given time. Often, additional information is being included as well. Basically, all information needed to carry out corporate actions, which are not technically reflected in the smart contract have to be processed off-chain. Thus, the design of the Off-Chain part of any tokenization is just as important as the On-Chain-components.

Moreover, even though the content of the off-chain database is often kept private and secured, the according governance processes need to be communicated transparently. Where and how exactly is the data stored? Which security standards are implemented? Who has access and how are entries being initiated as well as amended?

In this context the question of what is to be considered as «On-Chain» is crucial.

What are the minimum and optimum requirements to represent decentralization in a transaction system?

According to the new Swiss DLT law (link to the version in German) the integrity of the system has to be ensured by adequate technical and organizational measures such as the joint operation of the system by independent parties. According to the Swiss Blockchain Federation’s recent circular (01/2021) a minimum of three independent parties would be necessary. Often also only so called public blockchains are considered on-chain.

Generally, it seems fair to say that the integrity level of a system can be increased, the more distributed / decentralised it is (i.e. the more validators and consensus-relevant nodes exist), the more independent the respective parties are and the more transparent the system is designed. If and to what degree this is desirable for a tokenization project has to be evaluated individually.

Meanwhile, public (permissionless) blockchains show appreciable advantages regarding the interoperability of an ecosystem. A deeper analysis of the factor of interoperability will be conducted in the third article of this series of articles.

Phase 3: Continuation

Phase three describes the aspects of a security tokenization that come into effect after the token has been issued. Where is it stored, how can it be transferred and what can it be used for? These aspects are also where the potential benefits of a tokenization — efficiency gains, higher liquidity and more transparency (for details please see the first article of this series of articles) — are probably most directly represented.

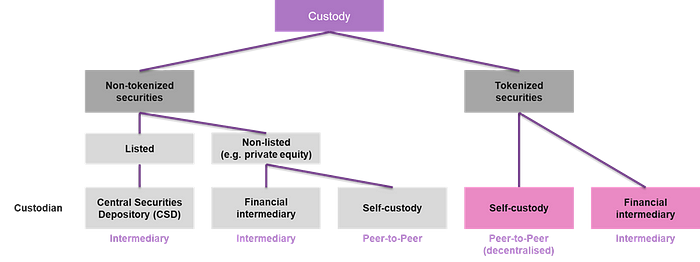

Custody

The custody of a security is closely linked to the various options of how to transfer the security. In the custody of listed securities, also referred to as intermediated securities (in German: Bucheffekten), apart from the investor, the following two actors are typically involved: financial intermediaries and a Central Securities Depository (CSD). The CSD is responsible for the safekeeping of the securities’ records. The holder of the asset itself does not have direct access to the security. He or she must rely on a financial intermediary that arranges all interactions with the CSD. In the case of custody of non-listed securities (e.g. private equity of SMEs), a distinction can be made between self-custody of the (physical) securities and custody with a financial intermediary.

Tokenized securities on the other hand do not necessarily need a financial intermediary or a CSD to keep the securities safe. The DLT-solution (i.e. the blockchain) represents the ledger respectively the records of the security. It is a transparent and immutable register for all transactions. The investor uses a so-called «private key» to access and transfer the tokens. It metaphorically serves as a digital fingerprint and enables the signing of transactions on a blockchain. Thus, the security itself does not change in a transaction. Only the access rights are being transferred to another key.

The private keys can be stored in a wallet. There is a broad range of technical implementations of wallets: desktop wallets, mobile wallets, paper wallets, hardware wallets etc. Moreover, some of the wallets also include functions that demand multiple signatures to carry out a transaction. To sum up, the wallets basically serve as a custody solution. Depending on the design of the wallet, the system allows peer-to-peer transactions. A token holder can transfer its securities to another investor without having to instruct a financial intermediary or CSD to change the ledger or even physically transfer the security.

The above explained transaction process has been applied in the case of utility and payment tokens for quite some time already. Historically, in the case of security tokens there was still a legal requirement for a written cession. This was one of the main obstacles for a broader adoption. However, with the recently enacted Swiss DLT law security tokens can now be issued as uncertificated register securities. This allows holding and transferring security tokens in a very similar way as utility or payment tokens; i.e. without a written cession. Please note that there are however important additional factors such as the whitelisting process (for details see section «Investor Onboarding»).

Even though the same basic principles are being applied, there are certain distinguishing factors between utility/payment tokens and security tokens. Unlike payment or utility tokens, the consequences of a private key being stolen or lost are less drastic in the case of security tokens. There are ways and means for a recovery. This does not mean that the private key is actually recovered. Generally, the way to “recover” a private key is to legally declare a key respectively its allocated tokens as void. From a technical perspective this often involves “freezing” or “blocking” a token after the legal action (off-chain) has been ratified. Then a new private key is issued and the corresponding tokens are reminted. From a legal perspective such solutions are conceivable as the rightful owner of a token generally had to go through a whitelisting process and can therefore be identified and contacted. Please note however that this process can be costly and lengthy. Hence, it should be treated as a measure of last resort.

Consequently, the decision to use an own wallet (self-custody) or a wallet of an institution (third-party custody) does not primarily depend on security aspects. Factors such as the user-friendliness of a custody solution and the integration into other trading systems could however become crucial. This is one part where custody solutions provided by traditional financial intermediaries could come into play. Either way, when choosing to tokenize an asset, the following important questions regarding custody arise:

- What wallet options are offered to investors?

- Which partnering financial intermediaries offer a third-party custody solution for the token?

- How easily could an investor switch its custody provider and what dependencies are built into the token?

Trading

The issuance of security tokens in the primary market usually serves financing purposes unless it is a tokenization of existing financing instruments. From an investors’ point of view, it is desirable that the issued security tokens can subsequently be traded on a liquid secondary market. Making sure that there is a credible possibility for an exit (i.e. disinvestment) is one of the most (if not the most) crucial investment criteria. As pointed out in the first part of this series of articles «higher liquidity» is often cited as one of the key benefits of a tokenization. However, the possibility to make security tokens tradable does not automatically lead to a liquid market.

A market is considered liquid if…

1. the spreads between the highest bid and the lowest ask price are small and

2. the execution of large orders does not cause significant price movements (slippage).The liquidity of secondary markets is basically enabled by a large number of market participants and/or the presence of professional market makers.

Traditional liquid financial markets have historically been facilitated by (regulated) exchanges. In regard to tokens, numerous central exchanges for payment and utility tokens have emerged in the market in recent years. However, for security tokens there are almost no central exchanges currently available. The reason why there are very few central exchanges for security tokens is mainly due to legal and regulatory restrictions. When trading security tokens on a central exchange, typically the same legal and regulatory requirements must be fulfilled as when trading classical securities on an exchange. In Switzerland, according to the Financial Market Infrastructure Act (FMIA), the following secondary markets require a license as a financial market infrastructure or at least a license from the Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA):

- Stock exchanges

- Multilateral Trading Facilities (MTF)

- Organized Trading Facilities (OTF)

- DLT trading facilities (new as of 08/2021; details to be defined)

Apart from «higher liquidity» another potential benefit regarding the trading of security tokens is directed to the aspect of timing. Depending on the exact architecture of the DLT solution and the token itself, it is potentially possible to trade on a 24/7-basis. This fact could trigger new market dynamics if adoption of DLT-securities/assets will be higher in future.

As the aspect of secondary market trading is so essential for security tokens it should be addressed by any tokenization ecosystem. What is their plan regarding building up a secondary market? Which option is proportionate to the respective tokenization project? The following paragraphs shall serve as a short overview of the different options.

Regulated secondary markets

Stock exchanges and MTF are referred to as trading venues under Swiss law and are suitable for non-discretionary, multilateral trading of transferable securities. In non-discretionary trading, the matching of buy and sell orders is based entirely on predefined rules (i.e. no human interferences in the matching is allowed or foreseen). On a stock exchange, the securities are listed and must go through a formal listing process. In contrast, there is no listing of securities on an MTF. In Switzerland, the two stock exchanges SIX (Swiss Exchange) and BX Swiss (Berne Exchange) enable trading of traditional securities.

The Swiss Parliament recently approved several DLT-related legislative amendments to pave the way for the establishment of DLT infrastructures and security tokens. As part of this amendment to the Financial Market Infrastructure Act (FMIA) (effective as of 08/2021), another category of financial market infrastructure was created in the form of «DLT trading facilities». This new category will allow multilateral, non-discretionary trading of DLT securities. It facilitates the building of a secondary market for the newly introduced uncertificated register securities (no written form requirement for transfer).

In contrast to stock exchanges and MTF, DLT trading facilities can offer one or more of the following:

i) Admit retail investors as participants

ii) Offer central custody services

iii) Carry out clearing/settlement of DLT securities

In addition, DLT trading facilities also allow the trading of payment and utility tokens. The category «Small DLT trading facilities» benefits from regulatory simplifications thanks to the limitation of volumes in trading, custody, and settlement.

OTF do not require a license under the Financial Market Infrastructure Act (Art. 43 FMIA), but may only be operated in Switzerland by banks, securities houses, and trading venue operators (all of which require a FINMA license). OTF are suitable for multilateral or bilateral discretionary trading of securities and other financial instruments. In discretionary trading, the operator has the right to intervene in the matching of buy and sell orders. This possibility often proves desirable, especially in the trading of less liquid markets (e.g. SME shares) to for example to make sure that no market disruptions are caused by big orders.

Non-regulated secondary markets

In a (distributed) peer-to-peer trading system, transactions are conducted directly among peers, each of which is aggregated through a system. An example of this is the bulletin board, which brings buyers and sellers together but leaves the execution of trades to the users. Bulletin boards do not qualify as OTF and therefore may not be operated only by banks and securities houses. In practice bulletin boards are often used by tokenization platforms to allow registered users to find buyers/sellers for the respective tokens on the secondary market.

A decentralized exchange (DEX), on the other hand, ensures that trades are always executed in accordance with a defined set of rules. Decentralized exchanges such as Uniswap (for ERC-20 tokens only) are using smart contracts to do so. Unlike the peer-to-peer system, users of decentralized exchanges cannot choose with whom to trade, as an automatic matching is performed. Please note that the trading possibilities via DEX might be restricted for example due to whitelisting requirements (for details see section «Investor Onboarding»).

At the moment, decentralised exchanges are generally considered of substantial risk. Therefore, institutional investors currently only have limited access to secondary markets of security tokens. Furthermore, issuing tokens that can be transferred without having identified both parties (i.e. without a technically required whitelisting including KYC and AML checks) is expected to be an obstacle for a future listing on any regulated form of secondary market. Hence, it is essential to take this into consideration before issuing a security token.

Figure 6 summarises all currently possible trading facilitators for security tokens in Switzerland. Please note that figure 6 shows only simplified criteria. The requirement for an authorisation is highly dependent on the exact design of the trading system and thus needs to be assessed individually.

Corporate Actions & Info

The use of a DLT infrastructure promises not only efficiency gains around the trading of security tokens (trading, custody, clearing, settlement), but also cost savings in connection with corporate actions. The following events count as corporate actions: dividend/coupon payments, par value repayment, share buyback, capital increase, capital reduction, stock split, reverse split, spin-off, M&A, IPO, and delisting. Depending on the event, shareholders may or must vote on these events.

To realize gains in efficiency related to the payment of dividends or coupons, smart contracts could be used. Automated payouts could realize cost savings for financial intermediaries, ultimately benefiting issuers and investors. However, for the automated payouts via smart contract, private or public stablecoins (Central Bank Digital Currencies, CBDC) would be advantageous to avoid a media switch to fiat currencies or having to use volatile payment tokens (for details see section «payment options»).

Another advantage of security tokens is that in case of equity tokens the share register is being digitized (by recording all transactions on the DLT infrastructure). As a result, the issuer always has access to an immutable and reliable shareholder register. In the case of non-listed SME companies, there have been cases where it was unclear who actually owns the shares. This often causes difficulties in M&A-transactions, eventually leading to higher costs.

Additionally, more and more tokenization ecosystems offer a possibility to hold the general assembly online. The respective voting could be taken digitally (e.g. via the security token) in order to optimize the processes in this regard. The exact technical implementations can differ and have to be analysed individually. Compared to traditional securities, the mentioned efficiency gains certainly speak in favour of tokenizing assets in the form of security tokens.

Summary

Phase one is all about preparing a security token offering in a sensible way. It also highlights the importance of analysing the needs of the project and matching these requirements with a respective ecosystem. Phase two is then about the details of the implementation and execution of a security token offering. Lastly, phase three sheds light on how the potential benefits of a tokenization could be harvested. Nevertheless, one has to remember that no matter how a tokenization project is being carried out, it is eventually only the wrapping paper of the security. The content will always be a traditional security such as a “normal” share, a bond or some other kind of asset.

Outlook

If an issuing company chooses to carry out a security token offering it is important to thoroughly assess the different options. This article should give any issuer but also any other stakeholder of a tokenization an overview of the relevant aspects of a security token offering. The choice of a specific network, group of partners or ecosystem always comes with a certain degree of dependency. One of the basic ideas of DLTs however, was to reduce these “silos” in the (financial) markets. While it is clear that some parts of any business proposition have to be protected it is also essential to allow as many interactions with alternative ecosystems and approaches as possible. Only this way can the technology eventually leverage its full potential. The technical term “interoperability” used in this context will be examined in more detail in the next article in our three-part series.

Stay tuned and let us know your thoughts on the topic at hand.

About the research project:

This article is the second part of a series of short articles pointing out some of the important aspects about tokenization, its possibilities, and challenges to change the current capital markets. The articles are part of a research project by the Eastern Switzerland University of Applied Sciences. The project aims to assess and combine the needs of all relevant market participants into a framework and to standardise the tokenization process. This shall eventually also define a certification process for future issuances.

The current project partners are representing various stakeholders of a tokenization: financial industry (fedafin, Hypothekarbank Lenzburg, PFLab by PostFinance), legal (Kaiser Odermatt & Partner, VISCHER, WalderWyss) and technology (Drakkensberg, KORE Technologies). The research project is co-financed by Innosuisse and open for additional project partners (details: www.digital-assets.ch). The goal is to unite as many industry leaders as possible to build a broadly supported standard for (truly) digital assets. This standard shall also include existing guidelines, handbooks and benchmarks.

Please note:

The article at hand has been independently written by the research partners from the Eastern Switzerland University of Applied Sciences. Hence, the content of the article does not necessarily have to represent the opinions of all project partners.

Authors:

Pascal Egloff, lecturer and project manager for Banking & Finance at the Eastern Switzerland University of Applied Sciences in St.Gallen. He is active in the fields of digital assets, corporate and project finance, financial technologies and innovation in banking.

Prof. Ernesto Turnes, head of the Competence Centre for Banking & Finance at the Eastern Switzerland University of Applied Sciences in St.Gallen, where his focus lies in the areas of digital assets, asset management, financial instruments, and innovations in banking. He is also chairman of a Swiss asset management company and a board member of a pension fund.